Character table

In group theory, a character table is a two-dimensional table whose rows correspond to irreducible group representations, and whose columns correspond to classes of group elements. The entries consist of characters, the trace of the matrices representing group elements of the column's class in the given row's group representation.

In chemistry, crystallography, and spectroscopy, character tables of point groups are used to classify e.g. molecular vibrations according to their symmetry, and to predict whether a transition between two states is forbidden for symmetry reasons.

Contents |

Definition and example

The irreducible complex characters of a finite group form a character table which encodes much useful information about the group G in a compact form. Each row is labelled by an irreducible character and the entries in the row are the values of that character on the representatives of the respective conjugacy class of G (because characters are class functions). The columns are labelled by (representatives of) the conjugacy classes of G. It is customary to label the first row by the trivial character, and the first column by (the conjugacy class of) the identity. The entries of the first column are the values of the irreducible characters at the identity, the degrees of the irreducible characters. Characters of degree 1 are known as linear characters.

Here is the character table of C3 = <u>, the cyclic group with three elements and generator u:

| (1) | (u) | (u2) | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ1 | 1 | ω | ω2 |

| χ2 | 1 | ω2 | ω |

where ω is a primitive third root of unity.

The character table is always square, because the number of irreducible representations is equal to the number of conjugacy classes. The first row of the character table always consists of 1s, and corresponds to the trivial representation (the 1-dimensional representation consisting of 1×1 matrices containing the entry 1).

Orthogonality relations

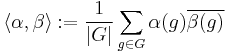

The space of complex-valued class functions of a finite group G has a natural inner-product:

where  means the complex conjugate of the value of

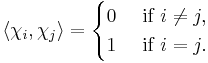

means the complex conjugate of the value of  on g. With respect to this inner product, the irreducible characters form an orthonormal basis for the space of class-functions, and this yields the orthogonality relation for the rows of the character table:

on g. With respect to this inner product, the irreducible characters form an orthonormal basis for the space of class-functions, and this yields the orthogonality relation for the rows of the character table:

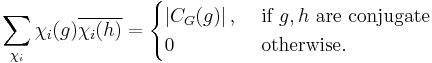

For  the orthogonality relation for columns is as follows:

the orthogonality relation for columns is as follows:

where the sum is over all of the irreducible characters  of G and the symbol

of G and the symbol  denotes the order of the centralizer of

denotes the order of the centralizer of  .

.

The orthogonality relations can aid many computations including:

- Decomposing an unknown character as a linear combination of irreducible characters.

- Constructing the complete character table when only some of the irreducible characters are known.

- Finding the orders of the centralizers of representatives of the conjugacy classes of a group.

- Finding the order of the group.

Properties

Complex conjugation acts on the character table: since the complex conjugate of a representation is again a representation, the same is true for characters, and thus a character that takes on non-trivial complex values has a conjugate character.

Certain properties of the group G can be deduced from its character table:

- The order of G is given by the sum of the squares of the entries of the first column (the degrees of the irreducible characters). (See Representation theory of finite groups#Applying Schur's lemma.) More generally, the sum of the squares of the absolute values of the entries in any column gives the order of the centralizer of an element of the corresponding conjugacy class.

- All normal subgroups of G (and thus whether or not G is simple) can be recognised from its character table. The kernel of a character χ is the set of elements g in G for which χ(g) = χ(1); this is a normal subgroup of G. Each normal subgroup of G is the intersection of the kernels of some of the irreducible characters of G.

- The derived subgroup of G is the intersection of the kernels of the linear characters of G. In particular, G is Abelian if and only if all its irreducible characters are linear.

- It follows, using some results of Richard Brauer from modular representation theory, that the prime divisors of the orders of the elements of each conjugacy class of a finite group can be deduced from its character table (an observation of Graham Higman).

The character table does not in general determine the group up to isomorphism: for example, the quaternion group Q and the dihedral group of 8 elements (D4) have the same character table. Brauer asked whether the character table, together with the knowledge of how the powers of elements of its conjugacy classes are distributed, determines a finite group up to isomorphism. In 1964, this was answered in the negative by E. C. Dade.

The linear characters form a character group, which has important number theoretic connections.

Outer automorphisms

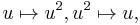

The outer automorphism group acts on the character table by permuting columns (conjugacy classes) and accordingly rows, which gives another symmetry to the table. For example, abelian groups have the outer automorphism  which is non-trivial except for 2-groups, and outer because abelian groups are precisely those for which conjugation (inner automorphisms) acts trivially. In the example of

which is non-trivial except for 2-groups, and outer because abelian groups are precisely those for which conjugation (inner automorphisms) acts trivially. In the example of  above, this map sends

above, this map sends  and accordingly switches

and accordingly switches  and

and  (switching their values of

(switching their values of  and

and  ). Note that this particular automorphism (negative in abelian groups) agrees with complex conjugation.

). Note that this particular automorphism (negative in abelian groups) agrees with complex conjugation.

Formally, if  is an automorphism of G and

is an automorphism of G and  is a representation, then

is a representation, then  is a representation. If

is a representation. If  is an inner automorphism (conjugation by some element a), then it acts trivially on representations, because representations are class functions (conjugation does not change their value). Thus a given class of outer automorphisms, it acts on the characters – because inner automorphisms act trivially, the action of the automorphism group Aut descends to the quotient Out.

is an inner automorphism (conjugation by some element a), then it acts trivially on representations, because representations are class functions (conjugation does not change their value). Thus a given class of outer automorphisms, it acts on the characters – because inner automorphisms act trivially, the action of the automorphism group Aut descends to the quotient Out.

This relation can be used both ways: given an outer automorphism, one can produce new representations (if the representation is not equal on conjugacy classes that are interchanged by the outer automorphism), and conversely, one can restrict possible outer automorphisms based on the character table.

References

- Rowland, Todd; Weisstein, Eric W, "Character Table" from MathWorld.